| Создатель Железного Дровосека От Апрельский тролль |

|

10 000 просмотров

17 декабря 2025 |

|

11 лет на сайте

5 июля 2025 |

|

10 лет на сайте

5 июля 2024 |

|

15 артов

8 сентября 2023 |

|

9 лет на сайте

5 июля 2023 |

|

#история #стихи #феминативы

Как мало поэтесс! как много стихотворок! Я подозреваю, что это стихотворение самым тесным образом связано с неприязнью Анны Ахматовой к слову «поэтесса» и с её стремлением непременно зваться поэтом. Затроллил корифей юное дарование. Ахматова уже много позже, со слов Лидии Чуковской, так говорила про Северянина: «Ему я тоже не нравлюсь. Он сильно меня бранил. Мои стихи – клевета. Клевета на женщин. Женщины – грезерки, они бутончатые, пышные, гордые, а у меня несчастные какие-то… Не то, не то…».О, где дни Жадовской! где дни Ростопчиной? Дни Мирры Лохвицкой, чей образ сердцу дорог, Стих гармонический и веющий весной? О, сколько пламени, о, сколько вдохновенья В их светлых творчествах вы жадно обрели! Какие дивные вы ведали волненья! Как окрылялись вы, бескрылые земли! С какою нежностью читая их поэзы (Иль как говаривали прадеды: стихи…), Вы на свиданья шли, и грезового Грэза Головки отражал озерный малахит… Вы были женственны и женски-героичны, Царица делалась рабынею любви. Да, были женственны и значит — поэтичны, И вашу память я готов благословить… А вся беспомощность, святая деликатность, Готовность жертвовать для мужа, для детей! Не в том ли, милые, вся ваша беззакатность? Не в том ли, нежные, вся прелесть ваших дней? Я сам за равенство, я сам за равноправье, — Но… дама-инженер? но… дама-адвокат? Здесь в слове женщины — неясное бесславье И скорбь отчаянья: Наивному закат… Во имя прошлого, во имя Сказки Дома, Во имя Музыки, и Кисти, и Стиха, Не все, о женщины, цепляйтесь за дипломы, — Хоть сотню «глупеньких»: от «умных» жизнь суха! Мелькает крупное. Кто — прошлому соперник? Где просто женщина? где женщина-поэт? Да, только Гиппиус и Щепкина-Куперник: Поэт лишь первая; вторая мир и свет… Есть… есть Ахматова, Моравская, Столица… Но не довольно ли? Как «нет» звучит здесь «есть», Какая мелочность! И как безлики лица! И модно их иметь, но нужно их прочесть. Их много пишущих: их дюжина, иль сорок! Их сотни, тысячи! Но кто из них поэт? Как мало поэтесс! Как много стихотворок! И Мирры Лохвицкой среди живущих — нет! Игорь Северянин, «Поэза о поэтессах», 1916 P.S. Очерк «Современной литературы» раскрывает тему подробнее, если кому-то интересно: https://sovlit.ru/tpost/pe0gg58xz1-ot-tretego-sfinksa Свернуть сообщение - Показать полностью

3 Показать 1 комментарий |

|

#история #матчасть #цитаты и, конечно, #политота

Интересная перекличка двух писем времён Руины с разных сторон конфликта, польской и украинской: Побуждаемый достодолжною преданностью к вашей королевской милости, господину моему и благодетелю, довожу до сведения вашего то, что могу видеть, и какой принимают здесь оборот дела, предлагая вместе с тем и средство, приличное настоящему времени и здешним обстоятельствам. ***Итак, во-первых, не изволь ваша королевская милость ожидать для себя ничего доброго от здешнего края! Все здешние жители скоро будут Московскими; ибо их перетянет к себе Заднепровье, а они того и хотят, и только ищут случая, чтобы благовиднее достигнуть желаемого. Они послали к Шереметьеву копию привилегий вашей королевской милости, спрашивая: согласится ли царь заключить с ними такие же условия? Правда, что у них главная цель состоит в том, чтобы не быть ни под властью вашей королевской милости, ни под властью царя. И этого они надеются достигнуть, ссоря и стращая вашу королевскую милость — царём, а царя — вашей королевской милостью. Посему и нужно, чтобы это коварство их обрушилось на их же головы; нужно вашему королевскому величеству непременно помириться с царём и сделать постановление с ним об Украине, хотя бы даже ваша королевская милость принуждены были уступить ему что-нибудь за Днепром, лишь бы только царь не брал козаков под своё покровительство. Впрочем, постановивши такие условия, мы должны хранить их во всевозможной тайне, чтобы козаки не обратились к Оттоманской Порте; ибо тогда они вовлекли бы вашу милость в большую и гибельную войну. Но если ваша королевская милость может иметь с царём такое соглашение, то благоволи вступить в Украину с сильнейшим войском. Не вынимая сабли, одним разом ты успокоишь их всех навсегда одним своим прибытием, а потом приведёшь их в такой порядок, что они не будут уже более своевольничать и вредить государству вашей королевской милости. Видит Бог, они слабы, милостивый, наияснейший король, господин мой, и примут всё, что ни возложит на них ваша королевская милость. А если бы они принимали это с неудовольствием, то надобно иметь под рукой татарское войско, чтобы оно вывезло их несколько фур в Крым; а с другой стороны войско вашей королевской милости доведёт их до нищеты, что заставит многих из них разойтись по деревням на Волыни и в Подолии. Таким образом, ваша королевская милость обезлюдит Украину, которая до тех пор, пока будет многолюдна, никогда не перестанет думать о том, как бы посредством интриг завлечь корону Польскую в новые войны; ибо я уже вижу, что борьба будет продолжаться до тех пор, пока не одолеет Украина Польшу, или Польша Украину. Здесь ужасное множество людей позорно злых и своевольных. Пока Украина не будет привелена к прежним своим началам, до тех пор не будет покою в Польше; то есть нужно, чтоб только несколько городов было в Украине, как прежде. Города будут хороши, когда их будет немного. Паны на Украине для своих честных выгод, предоставляя льготы, выманили крестьян из селений и сделали их своевольными. А покойный Хмельницкий своими войнами с намерением сделал их безмерно своевольными и поселил в них кровавую вражду к нам; а теперь они уже сами пожирают друг друга, одно местечко воюет против другого, сын грабит отца, а отец сына. Страшное представляется здесь Вавилонское столпотворение! Благоразумнейшие из старшин козацких молят Бога, чтобы кто-нибудь, или ваша королевская милость, или царь, взял их в крепкие руки и не допускал грубую чернь до такого своеволия. Ваша королевская милость может совершенно успокоить, даст Бог, одним приходом с войском своим. И ваша королевская милость имеет на то причину; потому что придёт как государь к своим подданым, лишь бы только они хотели до тех пор оставаться в этом мнимом подданстве вашей королевской милости. Есть несколько и других средств к обузданию этого своеволия, но я открою их, даст Бог, устно вашей королевской милости. Скажу, однако ж, милостивый, наияснейший король, главное средство, которое состоит в том, чтобы ваша королевская милость имел хорошую корреспонденцию с иностранными государями, и тем отнял у козаеов средство перебегать от одного государя к другому. Уже и Москва опомнилась, видя что двенадцать лет льётся наша кровь, кровь верных подданных вашей королевской милости, равно как и кровь подданных царя Московского и хана Крыского, а они между тем издеваются, перебегая от одного государя к другому. Хан Крымский находится на стороне вашей королевской милости; постарайтесь ещё приобрести приязнь и царя Московского. Этим ваша королевская милость преградит им путь так, что им не к кому будет обратиться. Султан Турецкий сделант то, чего захочет хан Крымский, потому что он отдал хану Крымскому весь Северный край в полное распоряжение. При сём нижайше и покорнейше прошу вашу королевскую милость, господина моего милостивого, извинить, если я написал что-нибудь не так осмотрительно; ибо всё, что ни написал, исходит от искренней и достодолжной моей преданности вашей королевской милости. Теперь у Хмельницкого главным распорядителем дел Ковелёвский, человек не глупый и пока преданный вашей королевской милости. Он-то и твердит, что козаки верно будут Московские; то же твердят и Миргородский полковник Грицко, обозный Шемечко и другие старшины. Впрочем, кто первый придёт с войском, тот верно и завладеет ими. Письмо коронного обозного Анджея Потоцкого королю Яну II Казимиру, 1659 год Иван Брюховецкий, гетман, с верным войском Запорожским. Господину сотнику новогородцкому верного войска Запорожского, атаману городовому и всему старшему и меншему товарству, также войтом, бурмистром, громадом и посполитым людем, так в самом городе Новогородке, как и по всем городам, и селам в сотне Новогородцкой будучим, доброго от Господа Бога здоровья желаючи, до ведома подаем, что за особым Божиим остерегателством мы уведомились и узрели, что Москали с нами хитро поступают, а с Ляхами помирясь, с обоих рук, се есть свое Московское и Ляцкое, нас войско Запорожское и весь народ християнский Украинский выгу6ляти, и Украйну отчизну нашу с основание разоряти постановили, и на то дав ляхом на наем войска чюжеземского четырнадцать милионов денег, присягли по нужде от них Москалей, яко от зломышляющих нам неприятелей, отлучилися есмы; однако мы не сами, но за згодною всее старшины и черни войска Запорожского радою, оных с крепостей Украинских гоняти умыслили есмы, занеже показалось нам то неслучно, чтоб мы о таком Московском и Ляцком нам и Украйне неприбылном намерении ведаючи, уготованное пагубы ожидати, а самих себя и весь народ Украинский до ведомого упадку о себе не радеючи приводити имели; и для того не теша болши общих неприятелей наших, с войском и со всем народом тое стороны, яко с братиею своею, к братцкому союзу пришедши, уже за милостию Божиею из знатных крепостей Украинских неприятелей Маскалей нашим промыслом, а згодным казаков и посполства послушанием и единогласным радением повыводили есмы, и их где ни есть в крепостях будучих будто ровным же подобием вывести могли прилежно, при помощи Божией, как сами промышляем, так и надежным особам радети и промысл чинити вручили есмы, и надежда на Бога, что в скором времяни и тех всех изгоним; понеже слобожане под рукою Московскою будучи, познав и увидя хитрую Московскую неправду, что им слобожаном равную с нами уготовили пагубу, их Московским защищением возгнушав, к нам войску Запорожскому склонитися и к любви братцкой приходити хотят: уже Недригайловцы, Олшанцы и Терновцы и иные к союзу братцкому с нами пристав, едино с нами разумеют. Но как к нам доходят ведомости: во многих городах и селех некоторые живущие люди таковым нашим радением около целости Украины отчизны гнушаючись, ссоры в мир всевают, а к соединению нас всех намеренному не приступаючи, вредителные росколы целости добра посполитого всчинают, и над своею братьею немилостивые мучителства и гонителства исполняют, чему с повинности началства нашего поборствуя, всякому даем на разсуждение: удобное ль то дело неприятеля в отчизне имеючи и оного единодушно не выгоняючи, междо собою един другого воевати и свою единоутробную братию, яко неприятелей, гонити, чего сам Творец наш Иисус терпети и всякого наступающего на кровь братню благословити не будет; понеже не от оного ль толко от домового несогласия и внутренних разностей, которые чрез прошедшия лета междо нами пребывали, Украйна отчизна наша милая изнищена и изобилное людское житие разорилось? Не радовались ли и не смеялись ли окресные наши враги, когда видели, что мы сами кровь свою проливали, и силные свои войска Запорожские, егда те одной стороны, а другие другой стороны держечись, умалились и на розных местах побеждени бывали? От чего ныне Господь сохранити да изволит! А так прилежно желаем и упоминаем, чтоб всяк, престав от недружбы и от гонителства на свою братию, любовь и согласие междо собою хранили, и своей старшине, належащую отдаючи повинность, зломыслящих нам неприятелей Москолей добывати, из городов выгоняти допомогали, чего и вторицею желаем и упоминаем. Письмо левобережного гетмана Ивана Брюховецкого жителям Новгорода-Северского, 1668 год Свернуть сообщение - Показать полностью

1 Показать 5 комментариев |

|

#история #русский_язык

Александр Шишков, известный радетель за чистоту русского языка, над которым за это подшучивали Пушкин и Белинский, не любил слово развиваться — ведь это калька с французского se devélopper. Слово, которое он предлагал взамен, современному человеку покажется едва ли не антонимом развитию — это слово прозябать. Дело в том, что это слово, старославянизм по происхождению, изначально имело значение «расти, прорастать» — обычно о растениях. Этимологически оно связано со словом зябь, т.е. «поле, вспаханное с осени под весенний посев». Само биологическое царство растений называли царством прозябаемых. Правда, уже во времена Шишкова слово прозябать воспринималось как архаичное или книжно-педантское. Его постепенно начали использовать в смысле «вести растительное, бессмысленное существование», сначала иронически, и потом, когда старое значение совсем забылось, уже без всякой иронии. Подробнее тут: https://etymolog.ruslang.ru/vinogradov.php?id=prozjabat 26 Показать 18 комментариев |

|

#матчасть #история

О РЕЧНЫХ ПУТЯХ И ВОЛОКАХ ДРЕВНЕЙ РУСИ. ЧАСТЬ ВТОРАЯ Представим, что мы в Рязани. Если мы не хотим тащиться вверх против течения Оки до Калуги, устья Угры или устья Жиздры, то мы должны «перепрыгнуть» в верхнее течение Оки таким образом: вниз по Оке - вверх по Проне (мимо города Пронска) - волок на Иван-озеро - вниз по Шату - вниз по Упе (мимо города Тулы) - вниз по Оке. То же самое Иван-озеро являлось историческим истоком Дона до того, как уровень воды в нём упал из-за пробития водоупорного глинистого пласта при строительстве Иваноозерского канала — из-за этой ошибки судоходство по каналу оказалось возможно лишь во время половодья, и после потери Азова из-за неудачи Прутского похода он был заброшен. Однако, даже в лучшие времена Дон в верхнем своём течении, в отличие от Шата, представлял собой не более чем ручей, периодически теряющийся в болотцах, и для судоходства был совершенно непригоден. В связи с этим на Дон из Оки выходили через приток Прони, реку Ранову: 1. Вниз по Оке - вверх по Проне - вверх по Ранове - вверх по Хупте - Рясский волок - вниз по Становой Рясе - вниз по Воронежу - вниз по Дону, до Таны с итальянскими факториями или прямо до Азовского моря. Для охраны этого пути (ну и для мыта, само собой) был основан город Ряжск. В наказе Ивана III к рязанской княгине Агриппине читаем: «А ехать ему Якуньке с послом Турецкимъ отъ Старой Рязани вверх Пронею, а от той реки Прони по Рановой, а из Рановой Хуптою вверх до Переволоки, до Рясского поля». 2. Вниз по Оке - вверх по Проне - вверх по Ранове - волок на Кочуровку - вниз по Кочуровке - вниз по Дону. Здесь волок сторожил город Дубок, но его, как и окрестные городки, уничтожила орда Мамая в ходе событий, предшествовавших Куликовской битве, и с тех пор этот край пришёл в запустение. 3. Вниз по Оке - вверх по Проне - вверх по Ранове - вверх по Полотебне - вверх по Мокрой Полотебне - волок на Дон - вниз по Дону. Волок около села Милославщина функционировал вплоть до начала XX века, его работа запечатлена на фотографиях, а деревянный пандус, по которому лодки затаскивали на междуречье, сохранился до сих пор. Для того, чтобы вернуться с Дона на Оку, можно было пройти этими путями в обратном направлении до Прони, а потом подняться по ней вверх до волока на Иван-озеро и спуститься в Оку по Шату и Упе, но можно было пройти и другим маршрутом: вверх по Дону - вверх по Быстрой Сосне (мимо города Ельца) - вверх по Дичне - вверх по Любовше - вверх по Переволочинке - волок на Пшевку - вниз по Пшевке - вниз по Зуше - вниз по Оке. Современные пороги на Быстрой Сосне — это рукотворное препятствие, остатки взорванной плотины; в Средние века их ещё не было. Из верхней Оки можно было выйти сразу в верховья Днепра, к Смоленску и волокам на Западную Двину 1. Вверх по Угре - вверх по Чернавке - волок на речку Пруды (на исторических картах это две реки, Волочовка и Готиновка) - вниз по Прудам - вниз по Осьме - вниз по Днепру. 2. Вверх по Угре - вверх по Волосте - волок на Вязьму - вниз по Вязьме (мимо города Вязьмы) - вниз по Днепру. Или на Десну, которая суть прямая дорога на Вщиж, Брянск, Случевск, Новгород Северский, Чернигов, Киев и далее «в греки»: 1. Вверх по Жиздре (мимо городов Перемышля и Козельска) - волок по берегу в обход Жиздринских порогов - вверх по Жиздре - вверх по Рессете - вверх по Лахаве - волок на Болву - вниз по Болве - вниз по Десне - вниз по Днепру. На реке Жиздре стояли города Перемышль и Козельск. 2. Вверх по Угре - вверх по Рессе - волок на Волоку - вниз по Волоке - вниз по Неручи - вниз по Болве - вниз по Десне - вниз по Днепру. Или на Сейм, который впадает в ту же Десну, минуя перед этим Курск (если идти через Тускарь), Рыльск и Путивль: 1. Вверх по Оке - вверх по Очке - Хамово озеро - вниз по Снове - вниз по Тускари - вниз по Сейму - вниз по Десне - вниз по Днепру. 2. Вверх по Оке - вверх по Очке - Хамово озеро - вниз по Свапе - вниз по Сейму - вниз по Десне - вниз по Днепру. Детали путей через Хамово озеро остаются предметом обсуждений среди специалистов. Хотя существует достаточно доказательств связи Посемья с Поочьем и Поволжьем, неизвестно, вытекала ли Очка прямо из Хамова озера, или брала свой исток поблизости, и была ли она достаточно полноводна в верхнем течении — если нет, то потребовался бы волок между Хамовым озером и Окой. Само Хамово озеро — реликтовый ледниковый водоём, который уменьшался из-за естественных геологических процессов и сведения лесов, пока не превратился в Самодуровское болото, а теперь и оно почти пересохло. Волок не обязательно должен находиться на водоразделе между великими реками вроде Волги, Оки или Днепра, или быть звеном на пути к такому водоразделу, как Яузский мыт или Волочёк Зуев. Некоторые волоки имели сугубо местное значение, обслуживая маршруты внутри большого речного бассейна. Были такие и в бассейне Оки. Там, где сейчас стоит город Наро-Фоминск, когда-то был Фоминский мыт. Волок в этом месте возник, вероятно, ещё в те времена, когда Коломна, которая запирает устье Москвы-реки, принадлежала Рязани. Владимирским и черниговским князьям был нужен путь, соединяющий их владения и проходящий мимо рязанских мытарей. Если мы отправляемся из Москвы, то маршрут в обход Коломны выглядит так: вверх по Москве-реке - вверх по Пахре - волок на Нару - вниз по Наре - вверх по Оке. После того как первый московский князь Даниил Александрович захватил Коломну, необходимость в этом обходном пути отпала. Однако Фоминский мыт не исчез: здесь проложили дорогу к Серпухову, основанному в устье Нары. Путь к Серпухову по Москве-реке и Пахре оказался короче и проще, чем движение против течения Оки от Коломны до Серпухова. Другой внутрибассейновый волок между притоками Оки соединял Москву с Тулой. От Тулы, которая стоит при впадении реки Тулицы в Упу, следовало идти так: вверх по Тулице - волок на Осётр - вниз по Осетру - вниз по Оке - вверх по Москве-реке. Обратно, из Москвы в Тулу, тоже удобно было идти этим путём, так устья Москвы-реки и Осетра недалеко друг от друга. Свернуть сообщение - Показать полностью

3 |

|

#история #политота #матчасть #из_комментов

Цитаты, которые я накопал для спора о возрасте этнонима "русские" в его современном смысле: … Захар Ляпунов с ратными людьми, с резанцы и с арзамасцы пошли под город под Заразской. А в городе в Заразском сидел полковник Александр Лисовский и с ним литовские ратные люди, и черкасы, и русские всякие воры. И как московские люди пришли под город под Заразской, на поле, и Лисовский со всеми людьми из города вышел на бой, и с резанцев и с арзамасцы был к него бой, и резанцев и арзамасцев побил и много живых поймал… Показать полностью

5 53 Показать 7 комментариев |

|

#матчасть #история #из_комментов

О РЕЧНЫХ ПУТЯХ И ВОЛОКАХ ДРЕВНЕЙ РУСИ. ЧАСТЬ ПЕРВАЯ Вверх по большим или порожистым рекам особо и не ходили. Для подъёма выбирали спокойные малые реки, иногда поднимая уровень воды на сложных участках с помощью временных плотин, и шли вверх бечевой или шестовым ходом. Некоторые реки становятся более удобными в половодье, другие наоборот ускоряют своё течение и становятся бурными и опасными. Судёнышки, которые использовали для таких путешествий — это не огромные волжские барки более позднего времени, и усилий их собственной команды было вполне достаточно. Так поднимались до места сближения водных бассейнов, где устраивали волок — разгружали суда, перетаскивали их и товары посуху и вновь загружали. Обычно при волоках были сёла или городки, жители которых зарабатывали себе на жизнь этой работой. Маршрут при этом следовало выбрать с таким расчётом, чтобы после преодоления водораздела оказаться выше по течению, чем пункт назначения. Конечно, тоннаж и осадку судов всё это сильно ограничивало. Предположим, нам нужно добраться из Новгорода в Москву. Путь вверх по Мсте нелёгкий, но зато самый короткий и имеет то преимущество, что выходит на Волгу выше устья Шоши, позволяя просто спуститься к нему по Волге без усилий. Маршрут таков: озеро Ильмень - вверх по Мсте, не доходя до порогов - Волок Держков на Боровичские озёра (каскад озёр Пелено-Люто-Шерегодро-Ситное-Ямное) - вниз по Ямнице - вниз по Удине - озеро Коробожа - вниз по Увери, возвращаясь в Мсту выше порогов - вверх по Мсте - озеро Мстино — вверх по Цне - волок на Тверцу (Вышний Волочёк) - вниз по Тверце - вниз по Волге - вверх по Шоше - вверх по Ламе - волок на Волошну - вниз по Волошне - вниз по Рузе - вниз по Москве-реке. Вместо Волошны могли подниматься из Ламы вверх по Большой Сестре, переволакивать в Гряду и спускаться в Рузу по Гряде и Озерне. Эти волоки с Ламы — Волок Ламский, наверное, самый знаменитый из всех. Лама и Волошня в месте наибольшего сближения мелки и имеют неудобные берега, поэтому волок соединял их не в этом месте, а там, где начинались их проходимые участки — между селом Иваново (бывшее Староволоцкое) и деревней Становище. Точно так же, как Вышний Волочёк соединял Тверцу и Цну вовсе не у истоков, где между ними всего 500 метров, но они представляют собой не более, чем ручьи. Кстати, в XVIII-XIX вв., уже после создания Вышневолоцкой водной системы, на малых судах вверх по Мсте тоже ходили. На реке работали артели бурлаков, а русло было насколько возможно спрямлено и благоустроено, что позволило отказаться от обходного пути через Боровичские озёра — товар просто обносили по берегу, а разгруженные суда поднимали через пороги проводкой. Правительство даже предоставляло субсидию за каждое вернувшееся из Петербурга судно в целях сбережения леса. Можно было также пройти Селигерским водным путём, как говорится, объехать на кривой козе: 1. Озеро Ильмень - вверх по Поле - вверх по Щеберехе - озеро Щебереха - волок на озеро Селигер - вниз по Селижаровке - вниз по Волге - вверх по Дёрже - волок на Белую - вниз по Белой - вниз по Рузе - вниз по Москве-реке. 2 («Демонская дорога», т.к. мимо города Демон, ныне Демянск). Озеро Ильмень - вверх по Поле - вверх по Явони - вверх по Чёрной - каскад озёр Истошное-Стромилово-Соминцево-Долгое-Волоцкое - волок на озеро Селигер - вниз по Селижаровке - вниз по Волге - вверх по Дёрже - волок на Белую - вниз по Белой - вниз по Рузе - вниз по Москве-реке. Этой дорогой в 1199 году двигалось посольство новгородцев во Владимир для примирения с великим князем Всеволодом Большое Гнездо, но глава посольства, новгородский архиепископ Мартирий Рушанин, не смог преодолеть весь путь и умер на берегах Селигера. Дёржа впадает в Волгу много выше, чем Шоша, и волок с неё на Белую короче Ламского, поэтому при движении от верховий Волги новгородцы предпочитали переволакивать суда здесь. Следует учитывать, что Явонь — быстрая, извилистая и порожистая река на протяжении первой половины своего течения. Возможно, в старину её перекрывали плотинами; остатки одной из них ещё можно увидеть перед Демянском. Остальные новгородские пути на Волгу выходят на неё ниже Шоши и непригодны для путешествия в Москву, но зато они пригодятся нам для обратного пути. Самый очевидный способ выйти на Волгу из Москвы — сплав вниз по Москве-реке и Оке, но для наших целей устье Оки расположено слишком низко. Для путешественника, направляющегося в Великий Новгород, наиболее удобны были маршруты через Клязьму, которые к тому же проходят мимо Владимира (именно так добралось до Владимира и, скорее всего, ушло из него вышеупомянутое новгородское посольство): 1. Вверх по Яузе (приток Москвы-реки) - волок на Клязьму (Яузское мытище) - вниз по Клязьме - волок на Сестру - вниз по Сестре - вниз по Дубне - вниз по Волге. 2. Вверх по Яузе (приток Москвы-реки) - Яузское мытище - вниз по Клязьме - вверх по Нерли Малой - вверх по Мосе - волок на Плещеево озеро - вниз по Вёксе - Сомино озеро - вниз по Нерли Большой - вниз по Волге. Первый путь менее трудозатратный, зато второй пролегает по людным местам и позволяет посетить по пути заодно ещё и Суздаль с Переславлем Залесским. Оба они активно использовались и в обратном направлении, для того, чтобы пройти из Волги в Клязьму, из Клязьмы в Яузу, а затем вниз по Москве-реке и Оке вернуться снова в Волгу — это позволяло вместо довольно пустынного и опасного в то время среднего течения Волги идти мимо многочисленных окских городов. После выхода в Волгу можно было воспользоваться Моложским водным путём: 1. Вниз по Волге - вверх по Мологе - вверх по Чагодоще - волок на Воложбу (Волок Хотеславль) - вниз по Воложбе - вниз по Сяси - Ладожское озеро - вверх по Волхову - озеро Ильмень. 2. Вниз по Волге - вверх по Мологе - вверх по Кезе - озеро Кезадра - волок на озеро Наволок - вниз по Тихомандрице - вниз по Съеже - вниз по Увери - вниз по Мсте - озеро Ильмень. Первый вариант лучше подходит для движения по направлению к Волге, поскольку идёт не через Мсту с её Боровичскими порогами, а через Сясь, где перед устьем Воложбы нужно преодолеть только последний из Костринских порогов, но возвращаясь в Новгород лучше воспользоваться вторым, так как это позволит избежать опасного подъёма по Волхову через Волховские и Пчевские пороги. Возможно, вместо Кезы можно было пройти вверх по Меглинке, через озёра Меглино и Островенское (речка Канава между ними — возможно, древний канал) и вниз по Радоли и Съеже в Уверь и Мсту. Хотя история и археология пока что этого не подтвердили, но такая протока между водоразделами нехарактерна для естественной гидрографической сети; энтузиасты успешно проходили этот маршрут на байдарках. Вместо Моложского водного пути можно было пройти тем маршрутом, на основе которого впоследствии была создана Мариинская водная система: вниз по Волге - вверх по Шексне - озеро Белое - вверх по Ковже - волок на Вытегру - вниз по Вытегре - Онежское озеро - вниз по Свири - Ладожское озеро - вверх по Волхову - озеро Ильмень. Но пороги на Волхове делают и этот путь более удобным для движения к Волге, а не наоборот. Была также пара способов попасть из Москвы на Волгу значительно выше по течению. Москвитянам легче всего было отвезти товары сухим путём по Волоцкой дороге до Волока Ламского, погрузиться на судно уже там и добраться Волошной, Рузой и Белой до волока на Дёржу. Но нам по условию задачи нужно вернуть в Новгород наше судно, которое стоит в Москве, так что придётся повозиться: 1. Вверх по Москве-реке (почти до истоков) - волок на Гжать - вниз по Гжати - вниз по Вазузе - вниз по Волге - вверх по Тверце - Вышний Волочёк - вниз по Цне - озеро Мстино - вниз по Мсте - озеро Ильмень. 2. Вверх по Москве-реке, но не доходя до дальних истоков поворачиваем в Рузу - вверх по Рузе - волок на Яузу (приток Гжати) - вниз по Гжати - вниз по Вазузе - вниз по Волге - вверх по Тверце - Вышний Волочёк - вниз по Цне - озеро Мстино - вниз по Мсте - озеро Ильмень. Взводное движение по Москве-реке не было чем-то диковинным и редким. Для большинства жителей Поочья оно было проще мороки с волоками, до которых ещё надо подняться по Клязьме, даже несмотря на необходимость преодолевать быстрое течение. Интереснейшее известие об этом оставил Павел Алеппский, описавший сплав по Оке от Калуги до устья Москвы-реки и подъём по Москве-реке до Коломны: «Мы еле могли сделать те пятнадцать верст до наступления вечера. Не успели мы достаточно оплакать себя по причине усталости, говоря: "это только пятнадцать; где же проехать еще сто шестьдесят пять?" как вдруг навстречу нам явилась радость: нас встретил драгоман, знающий по-гречески и по-русски, человек почтенный, пожилой, присланный от патриарха и царского наместника с поручением отправить нашего владыку-патриарха на царском судне по реке Оке, текущей подле Калуги, с полным спокойствием и удобством, в каменную крепость, по имени Коломна, известную, как епископская кафедра, в недалеком расстоянии от Москвы, чтобы мы оставались там, пока не прокатится моровая язва.» «В пятницу, 11 августа перед полуднем корабельщики повезли нас на веслах по течению вышеупомянутой Оки, которую они называют Окарика и которая как мы сказали, течет по направлению к Москве. В этой Калуге стоит множество судов, на коих перевозят продукты в Москву; все они покрыты широкою древесною корой, которая лучше деревянных досок. <...> Река делает множество изгибов, и потому мачт не употребляют, но имеют нечто в роде толстых и длинных копий с железным острием, кои погружают в воду, и корабль быстро идет. Если, случалось, он приближался к берегу и садился на мель, то его сдвигали также этими копьями с большим усилием ; а когда поднимался сильный ветер, люди выходили и тащили суда веревками, идя по берегу.» «Знай, что от обилия рек и источников, впадающих в эту реку Оку, она в некоторых местах становится очень широка, величиной с египетский Нил и даже больше, как нам говорил один из наших спутников. По причине ее большой ширины случалось, что мы шли иногда на глубине лишь около двух пядей, и часто в таких местах судно становилось на мель и не двигалось, так что янычары (стрельцы - прим.), раздевшись, входили в воду и благодаря своей силе, ухищрялись сдвинуть судно, в то время как их товарищи сверху действовали своими канджа, то есть длинными копьями с острыми наконечниками, пока наконец не сдвигали его с места и не отводили на глубину. Когда случался по временам сильный ветер, они также сходили с судна и тащили его на веревках, идя по берегу. Вскоре мы расстались с описанною рекой и вошли в известную реку Москву, которая течет от города Москвы и впадает в эту реку. <...> С тех пор, как мы вошли в Москву-реку и до высадки нашей, суда тащили веревками с берега, по причине стремительности ее течения и большой глубины.» Этот путь активно функционировал и в обратном направлении, из Вазузы и Гжати по Москве-реке вниз. Именно так, из верховий Днепра через Лосьминку, Вазузу и Гжать, прошёл Андрей Боголюбский, когда переносил Владимирскую икону Божьей матери из Вышгорода под Киевом во Владимир. Надо сказать, Вазуза вообще своего рода естественная распределительная станция — по её притокам из бассейна Волги можно перейти в бассейн Москвы, бассейн Днепра и бассейн Западной Двины — но пользовались этим в основном киевляне, смоляне и суздальцы, а затем москвитяне; у новгородцев было и сообщение с западными странами по морю, и более короткие пути в Западную Двину и Днепр. Свернуть сообщение - Показать полностью

15 Показать 5 комментариев |

|

#матчасть #история

Катастрофическое нашествие бедуинских племён бану хиляль и бану сулайм на Северную Африку, подкосившее земледельческую культуру этой территории (а для самих бану хиляль и бану сулайм — славное и великое время, воспетое в эпосе), имеет собственное название — Тагриба. 3 Показать 1 комментарий |

|

#история #ГП #матчасть

Книги XVI века, в которых появляется слово Salazarus (один и тот же текст на второй и третьей картинках, какой-то алфавитный список). Вроде имя, хотя я не уверен. Потом на досуге переведу.  Показать полностью

3 34 Показать 15 комментариев |

|

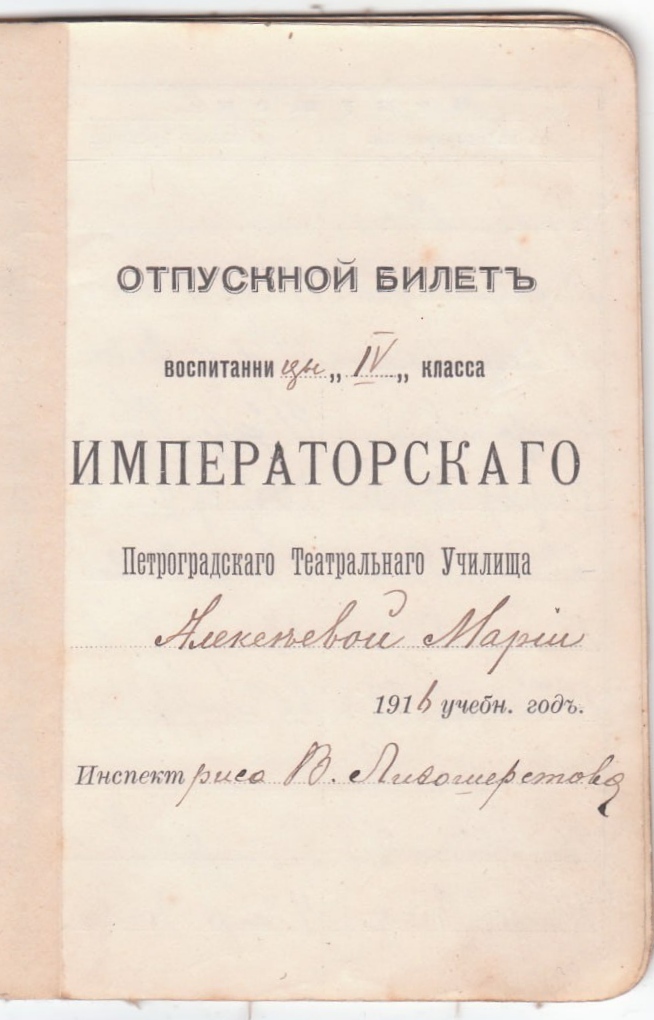

#русский_язык #история #пики #из_комментов (Пикабу)

Какое предусмотрительное Инспект  16 Показать 20 комментариев из 46 |

|

#русский_язык #ягодки #матчасть #история

Сереборинный цвет в старорусском языке — это не серебряный. Это изжелта красный, цвет шиповника: Название «шиповник» и варианты «шипок», «шипица», «шипец», «шипичник», «шипишник», «шиповный цвет», «шупшина» происходят от несохранившегося прилагательного *шиповьный, образованного от праслав. *šipъ — шип — «стрела, остриё, колючка», и не имеющего надёжной этимологии. Название «свороборина», «своробовина» (изменённые «свербалина», «сербелина», «серберина», «сербарин», «сербаринник», «сереборенник») произошло от слова «сво́роб» — «зуд», из-за волосистости семян, их вкусовых качеств или действия на кишечник и связано с чередованием гласных с «свербе́ть» от «сверб» — «зуд», от праслав. *svьr̥bĕti, сравнимого с др.-в.-нем. swērban — «крутиться, стирать», латыш. svārpsts — «сверло», др.-исл. svarf — «опилки», гот. af-swairban — «смахнуть». 14 Показать 6 комментариев |

|

Показать 3 комментария |

|

#история #матчасть и потенциально #политота

Об истоках наименования "Московия" (де-факто — просто перевод на латынь русского выражения "Московское государство", "Московская земля"):  Показать полностью

6 62 Показать 2 комментария |

|

#камешки #история #матчасть

Попытался разобраться, откуда уши растут у мифа о том, что Генрих V носил рубин Чёрного принца на шлеме в битве при Азенкуре. Нашёл самое раннее упоминание этой легенды, и неожиданно речь там вовсе не про Азенкур:  Этот сюжет приписывается самому Эдуарду Чёрному принцу, якобы он носил рубин в битве при Креси. Книжка от 1844 года, т.е. вышла годом ранее, чем «A Hand-Book for Travellers in Spain», труд Ричарда Форда, породивший испанскую легенду происхождения рубина Чёрного принца. В последующих источниках сначала к упоминанию принца Эдуарда и битвы при Креси добавляется аналогичный эпизод, только при Азенкуре с участием Генриха V, а потом про Чёрного принца забывают, и остаётся только Генрих — очевидно, из-за хронологической несостыковки, битва при Креси была гораздо раньше, чем битва при Нахере, после которой, согласно испанской легенде, принц Эдуард получил свой рубин. 4 Показать 2 комментария |

|

Показать 2 комментария |

|

#матчасть #история #из_комментов

1. Разные исламские историки дают два разных указания о племенной принадлежности Бейбарса (точнее, современные историки таким образом интерпретируют их сведения): آلبرلى (برلى) и اوغلى برج. 2. Часть историков интерпретирует آلبرلى как «олберлик» («Ольберы» в древнерусских источниках) — кыпчакское племя, кочевавшее на реке Ахтубе (территория современных Волгоградской и Астраханской областей), а اوغلى برج считает указанием на условную мамлюкскую «династию» Бурджитов, к которой принадлежал Бейбарс. 3. Другая часть историков интерпретирует اوغلى برج как указание на то, что Бейбарс был родом из племени Бурджоглы («Бурчевичи» в древнерусских источниках), которое кочевало вблизи от Днепра, на левом берегу реки. Указание на آلبرلى они считают ошибочным или неясным. 4. Именно на последнюю гипотезу опираются казахи, когда приписывают себе Бейбарса, потому что: «Этноним бурдж-оглы сохранился в этнонимии евразийских степей как род берш (берч) племени алчин Младшего жуза и род борчи (боршы) племени аргын Среднего жуза казахов». Однако мало того, что это спорно само по себе, так ещё и секретарь Бейбарса, чьи сведения донёс до нас Ибн Халдун, писал совершенно определённо: «Эти [одиннадцать племен], а Аллах знает лучше, составляют только кыпчакские разветвленные племена. А они те, что находятся в западной стороне их [кыпчаков] северной страны», и что султан Бейбарс, вышедший из среды этих кыпчаков, «относится к тюркам, привезённым в Египет из той западной области, а не со стороны Хорезма и Мавераннахра». 5. Есть ещё меньшинство учёных, которые считают, что Бейбарс относился к какому-то маленькому и малоизвестному племени барали/берели/бёрили (разные варианты прочтения слова برلى, которое приводят Ибн Шаддад и ан-Нувайри, и которое другие учёные считают просто укороченным آلبرلى). 6. К какому бы племени ни относился Бейбарс, в какой-то момент оно предприняло попытку миграции и попросило у вождя туркоманов Анаса позволения пройти через земли этого племени к Судаку (возможно, имеется в виду Судакское море, т.е. Азовское море). Анас-хан притворно согласился, но потом напал на кыпчаков и продал их в рабство в Судаке. А мечеть в Солхате никакого отношения к Бейбарсу не имеет. В арабских источниках, в частности ал-Макризи, сообщается, что на постройку мечети в Крыму деньги в размере 2000 динаров дал правитель Египта, однако не указывается его имя, зато чётко указан 1288 год. У Ибн ал-Фората уточняется имя султана, ал-Малик ал-Мансур (т.е. Аль-Мансур Калаун): «на этой мечети были начертаны прозвища султана ал-Малика ал-Мансура». Я неправильно сказал, Бейбарс считается представителем "династии" Бахритов. Тем не менее, египетских "бурджоглы" часто рассматривают как социальный термин, хотя есть и версия, по которой это название восходит к кыпчакскому племени. Свернуть сообщение - Показать полностью

1 |

|

#матчасть #история #ГП

Особенности национальной аппарации: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Tay_al-Ard https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Kefitzat_haderech https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Shukuchi 1 Показать 6 комментариев |

|

#история #пики #из_комментов

Слепил для дискуссии в Дзене, пусть тут тоже полежит (-: 10 Показать 13 комментариев |

|

#матчасть #история #ГП #магия_и_право (хотя тут очень косвенно)

Отправная точка для изучения исторических английских законов о наказании за обезображивание лица: тыц Займусь этим позже. Наверное, когда где-нибудь в очередной раз вспыхнет дискуссия о том, кто больше накосячил, Гермиона или Мариэтта (-: P.S. И ещё вот сюда: тыц 3 Показать 15 комментариев |